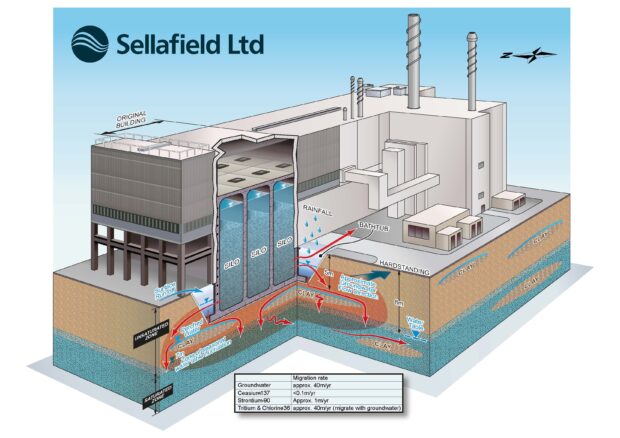

Sellafield’s legacy waste store, the Magnox Swarf Storage Silo, leaked radioactive liquor into the ground in the 1970s and in 2019 a new leak was discovered.

Our experts are pioneering new ways to help understand and manage what’s going on in the ground below it.

Curiosity around what comes back up after you drop a lure into deep water is a human instinct as old as, well, humans. Whether it’s a fish hook, a depth gauge or powerful ‘fishing magnets’, we all want to know more about what lies in the unseen depths below.

John Heneghan, contaminated land specialist in Sellafield’s Remediation team, gets to satisfy this curiosity in one of the most challenging, complex environments imaginable: under the ground of the Magnox Swarf Storage Silo, officially the most hazardous building on the Sellafield site.

John and his team have been pioneering a new method of extracting water samples from multiple depths under the silo to build a scientific picture of what exactly is moving around in the substrata.

Like a Time Team forensic investigation, they create a detailed picture of what’s happened at the scene using a matrix of tiny clues. But instead of a piece of pottery, some ancient seeds or a stone carving, John is looking for radionuclides and other ‘fingerprint’ qualities in water samples such as its electroconductivity or the levels of dissolved oxygen.

There’s nothing new in drilling boreholes at Sellafield to collect groundwater samples – we’ve been doing it for decades. It was the older generation of sampling boreholes which confirmed the impact of the first underground leak from the silo in the 1970s. The liquor released then was over 50 times more radioactive than the liquid seeping out now.

That’s because the original batch of liquor had been covering the radioactive offcuts from Magnox nuclear fuel rods for years, building up radioactivity like a slow-cooked stew.

Today’s liquor is far more diluted, not only because of the radioactive half-life of the waste put in there in the 1960s, but also because we’re constantly topping up the silo with demineralised water to keep the waste safely submerged. Liquor is seeping out of an unseen, unreachable crack at a rate of 1.7 litres per minute – so that’s the rate we fill at the top.

Thankfully, our planet has done a great job in being the first line of protection.

Directly underneath the silo is clay, which naturally binds in Caesium. This radioactive isotope accounts for around 95% of the radioactive content of the liquor.

That means that the vast majority of the radioactivity is already locked in the ground under the silo rather than moving around via groundwater.

Some radionuclides are more mobile though, which is where John’s team comes in.

“We track the movements of isotopes such as Tritium, Chlorine-36 and Strontium-90. Some of that is still moving around underneath the silo from the liquor deposited in the 1970s and some from the newer liquor leaking now – our science allows us to determine which is which.”

The recent technological breakthrough has been in understanding what is happening at different layers in the ground.

Beneath the silo are multiple individual layers of sand, clay and gravel sitting on sandstone bedrock about 45 metres down. These layers have tiered up over millions of years as glaciers tumbling down from the fells or sweeping in from the Irish Sea have brushed their deposits back and forth to build up a geological ‘trifle’.

“Our old boreholes provided a groundwater sample from one particular point of the well, so only gave us insights into a very specific layer in the really complex geology.

The new technology, the Morwick G360 multi-point system, allows us to pinpoint positions and extract samples at different heights from the same borehole, meaning we can understand what’s happening in individual layers of sand, clay and gravel and build far more intelligence about the rate and direction of individual flows,” says John.

The borehole has up to 6 different sealed tubes positioned at varying heights for samples to be pumped up to the surface to be transferred for laboratory analysis.

The system was developed over 10 years by the internationally-leading Morwick G360 Group at the University of Guelph in Ontario, Canada.

Sellafield Ltd commissioned the first trial in the UK before installing it on the Sellafield site in November 2023. This was the first time in the world it had been deployed on a nuclear site.

Sellafield is now collaborating with other nuclear sites such as Savannah River and Hanford in the US to see if it can help there.

In all 7 new boreholes were drilled for the new kit by specialist firm GeoSonic Drilling, supported by the i3 consortium. The deepest borehole was 50 metres down – that’s the same height as Nelson’s Column. Drilling deep holes on a congested nuclear site with a history like Sellafield’s is as complicated as you would imagine.

“We’re always mindful of the risk of service pipes both new and old being buried in the ground. These could be electrical cables or water pipes and hitting one of those could have safety risks not only for the people doing the drilling but for running the facilities on site,” says John.

We therefore plan extensively, mapping the area with all the intelligence we can gather by delving into the site’s history. Drilling trials were conducted off-site up in Alloa, Scotland, including a test installation of the new well system. Test holes were also dug on the Sellafield site at each drilling location before we deployed the drill rig.”

Nevertheless, there were some surprises.

“We came across a real rat’s nest of legacy services and cable ducts that were put in there back when the site was being used as a munitions factory in the Second World War,” says John.

It’s all been worth the effort though. In the months since analysis has started on the new pinpointed samples, John and his team have been able to build a far more detailed picture of what’s happening underground.

People will be understandably concerned about a leak of radioactive material on the Sellafield site – and it is an issue Sellafield and its regulators the Environment Agency and Office for Nuclear Regulation are taking incredibly seriously. But we are confident that there is no current risk of it harming anyone off-site or entering water supplies, which are sourced miles away, uphill from the Sellafield site (and water can’t flow uphill).

Instead, any contamination will move very slowly underground on the Sellafield site (typically at a rate of around a metre per year for strontium). It is slowly heading towards the sea directly next to Sellafield, where it would be massively diluted and pose no risk to the public.

“All of the intelligence we’ve gathered so far using the new kit has been reassuring – we are building a far more detailed and realistic assessment of risk,” says John.

Nevertheless his team are exploring ways to stop the underground movement all together.

“We are exploring whether it’s possible to bind in the radionuclides using chemical treatments – a bit like the clay does with Caesium.

By injecting material into the ground we may be able to ‘soak up’ the strontium and other radionuclides so it sits in the ground rather than moving through the groundwater” says John.

What then happens to the contaminated ground under the site is another issue, just like it is for many brownfield industrial locations. Decisions will need to be made on the safest and most sustainable solution.

But rest assured that with experts like John on hand, any decision will be informed by a wealth of factual evidence.

++Update May 2025++

Since writing this blog, the Nuclear Decommissioning Authority (NDA) and Sellafield Ltd have been collaborating with the United States Department of Energy’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory on the opportunities presented by the technology outlined here.

A two-day workshop has been held involving an international group of researchers, site operators, government agency staff, practitioners and regulators.

The focus was on the vertical delineation of contamination in aquifers and the potential that multi-level sampling has to offer more detailed monitoring information. It considered the trade-offs in cost, data resolution and technical constraints. The work being done at the Magnox Swarf Storage Silo (MSSS) was one of the case studies examined at the workshop

A key conclusion was that:

Multi-level systems are not without their own challenges, and may not be necessary at all remediation sites, but they are likely to be critical to effective remediation of complex sites.

The workshop organisers are now developing a strategy on how best to advance the technology in appropriate locations and the key findings are being presented at the 2025 RemPlex Global Summit.

Recent Comments