In the UK, we’ve been doing things that generate radioactive waste for decades – including electricity generation, medical treatments, defence, and a whole range of other activities. It’s important to keep track of all that waste.

For me, it wasn’t a conscious decision to get into the radioactive waste disposal business. Sometimes these things just happen! I did physics at university, and a PhD at Culham Centre for Fusion Energy. I was doing geophysics work when I found out about a Senior Inventory Manager role here at Radioactive Waste Management (RWM).

I’ve stayed in that role now for seven years. I really enjoy the mix of technical, analytical work, using my physics background, and addressing interesting challenges; for instance, working out what information we need, to be confident we can safely dispose of radioactive waste.

More than 90 percent of the radioactive waste in the UK today (by volume) can already be safely disposed of in suitably authorised and permitted landfill sites, or in the Low Level Waste Repository (LLWR) in Cumbria. The rest of the waste is more radioactive and will stay that way for longer, and so needs a safe, secure, long-term solution. At RWM, we’re going ahead with a plan to safely and securely dispose of this waste in a Geological Disposal Facility (GDF).

An important part of my team’s role is regularly updating our estimate of how much waste a GDF will need to accommodate. We call this estimate the Inventory for Geological Disposal (IGD). It sounds like a job that’s all about the numbers, but I actually spend a fair amount of time out and about dealing with people, helping to improve our data and how we communicate about it.

To estimate how much waste will need to go in a GDF, first we need to know how much waste already exists in the UK today. The Nuclear Decommissioning Authority are a big help with this – they take stock of the UK’s radioactive waste every three years and report their findings in the UK Radioactive Waste Inventory (UKRWI).

This is one of the world’s most comprehensive inventories. The level of detail is incredible. It gives me and my team a really solid foundation to build on.

Where is the waste now?

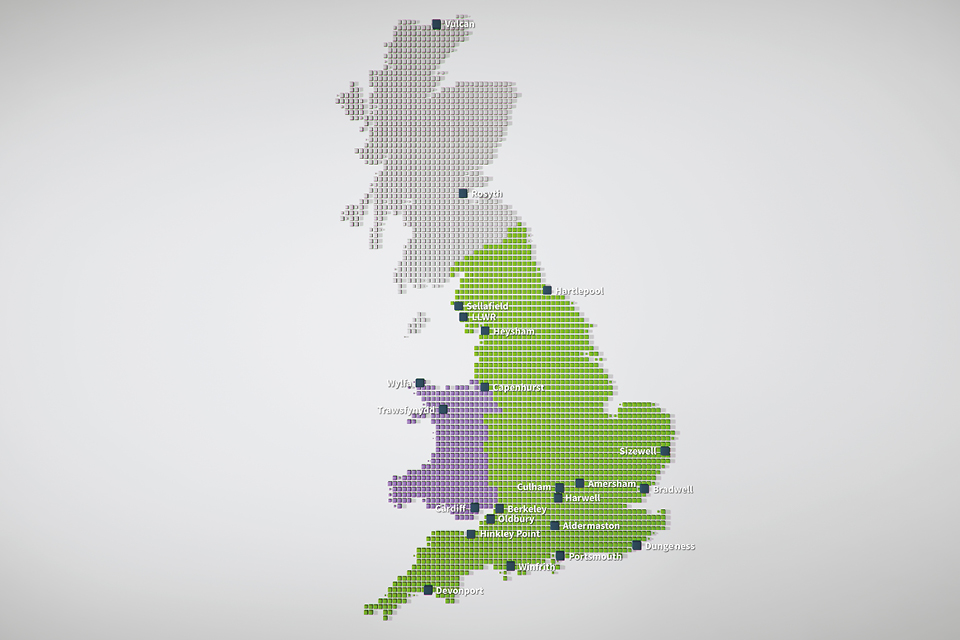

The most recent UK Radioactive Waste Inventory, in 2020, confirmed that waste destined for a GDF was being stored at a range of sites around the UK.

The highest volume of higher-activity radioactive waste in the UK is currently kept in specialised storage facilities at Sellafield in Cumbria. At Sellafield, used fuel from nuclear reactors is reprocessed to separate out any material that could still be useful. All the UK’s high level radioactive waste is a by-product of this reprocessing.

Because high level waste is generated at Sellafield, and most of the UK’s high level waste experts work there, Sellafield has developed safe and secure facilities for storing radioactive waste. After Sellafield, the next most significant stores of higher-activity radioactive waste are at nuclear power stations.

What will go into a GDF

As soon as the UK Radioactive Waste Inventory (UKRWI) comes out, we take that dataset and start combining it with additional information to produce the Inventory for Geological Disposal (IGD).

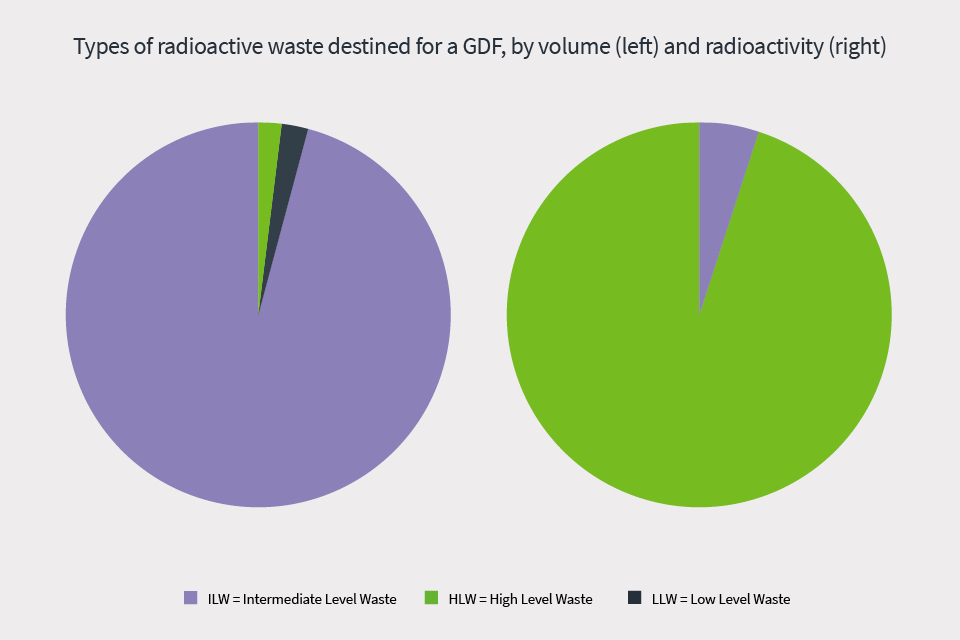

It’s not unusual for people to get the UK inventory and the GDF inventory mixed up. The main difference is that the UK Radioactive Waste Inventory includes all kinds of radioactive waste, while the Inventory for Geological Disposal only includes waste that we think will need to go in a GDF. So to produce the IGD, first we take the UKRWI and remove any low level and very low level waste destined for safe disposal at the Low Level Waste Repository (LLWR), or at other licensed landfill sites.

Then we get to the complex part. A GDF is highly likely to contain waste that doesn’t appear in the UKRWI yet. Some of this is material that already exists but isn’t considered to be waste (such as any spent fuel that is not reprocessed), and some hasn’t been generated yet (such as waste from new nuclear power stations, like the one currently being built at Hinkley Point C).

Part of my team’s job is calculating how much this waste will add up to by the time we complete a GDF.

Comprehensive and transparent

The latest UKRWI came out in early 2020, so I’m working on the next GDF inventory right now. The data always provides useful information. For example, if we stopped generating nuclear power today, it wouldn’t significantly reduce the volume of waste destined for the GDF. Based on the current numbers, about 90 percent of the volume of a GDF’s waste would be from nuclear plants that are currently operating, or that have already shut down.

Also, the total volume of the most recent IGD was less than 10 percent of the corresponding UKRWI. It’s good to know only a fraction of the UK’s volume of waste falls into the higher-activity category, destined for a GDF.

The UK’s radioactive waste inventories are among the most transparent in the world. We have a practical use for the IGD, to help us plan ahead for a safe and effective GDF, but the IGD and UKRWI are also useful for anyone who wants to know how much radioactive waste there is in the UK, where it is, and how we plan to deal with it.

Recent Comments